I met with Artist Lydia Halcrow in Bradford-on-Avon last week, to take a walk along the Bristol Avon. My first memory of Lydia must be from around 15 years ago, walking and talking together about climate breakdown, our anxieties, and the ways we hoped to address them in our work. Since then our paths have crossed multiple times, from exhibiting together (including A Gathering of Unasked Possibility, Bristol in 2019), to carrying out residencies alongside each other with Groundwork Gallery in Norfolk in 2024.

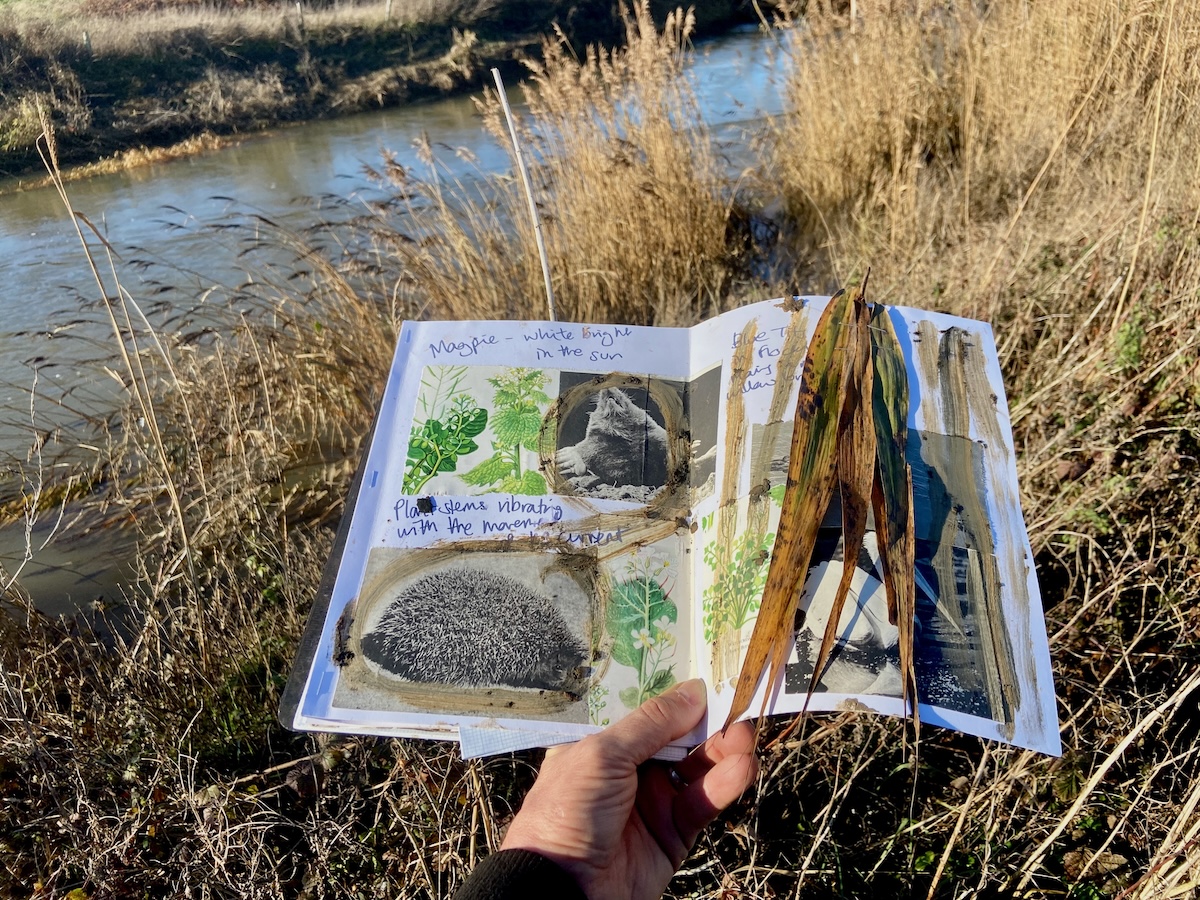

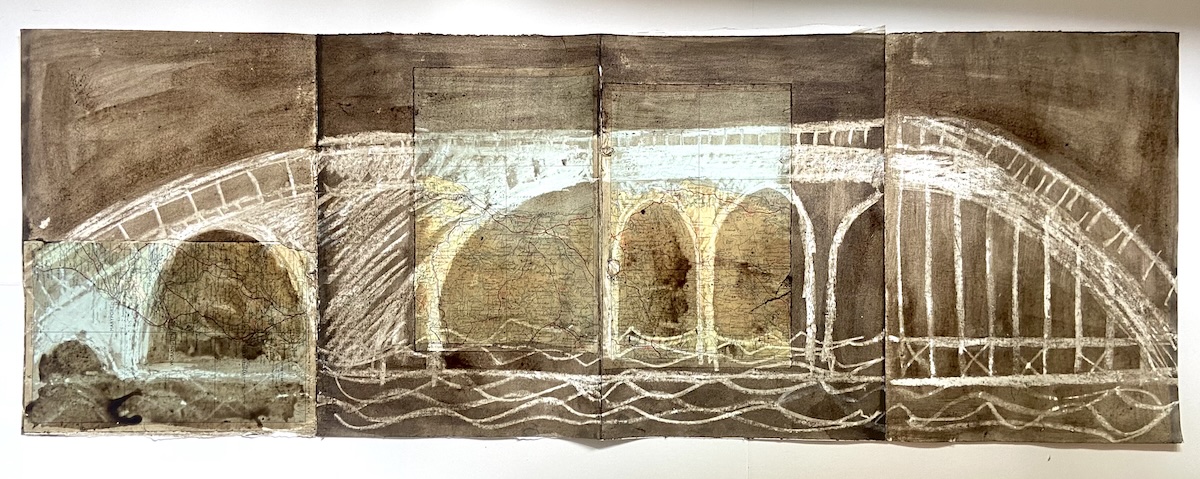

Lydia is a Bath-based artist, who exhibits widely, and whose practice explores ‘ ways of collaborating with a place through my walking body.’ Much of Lydia’s work in the past has taken place with river estuaries. In the introduction to her doctoral thesis she describes her research project as ‘...the culmination of six years of frequent walks along the Taw Estuary in North Devon.’

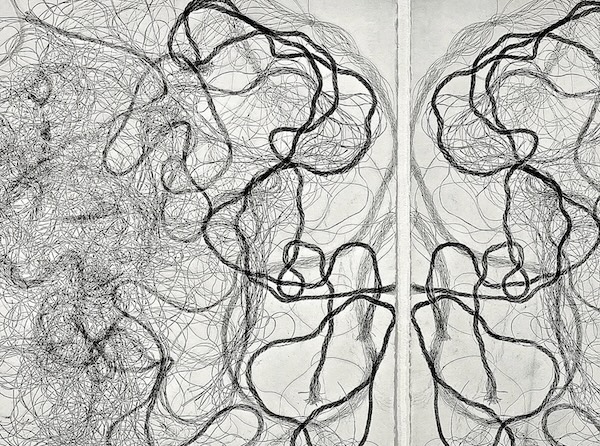

‘… the work and the contextual writing explores multiple strands that weave together and meander in forms that echo the experience of walking, the estuary itself and my childhood memories of this place. All are inextricably entangled with my experience of the Taw, the residue of the estuary on my walking body, and the trace of my body within the estuary.’

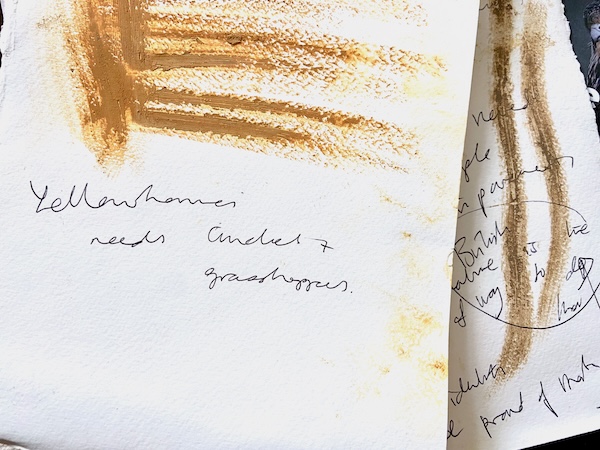

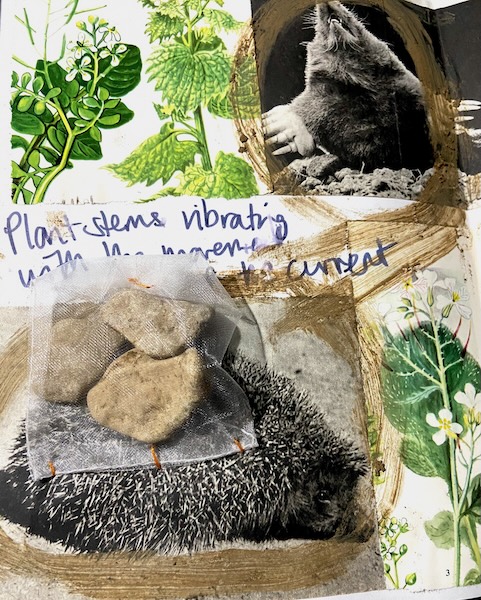

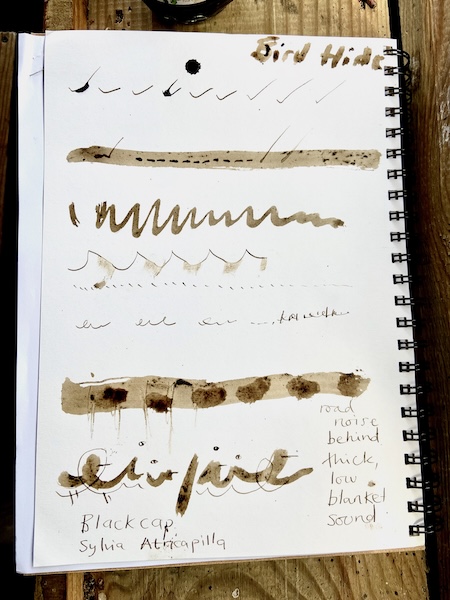

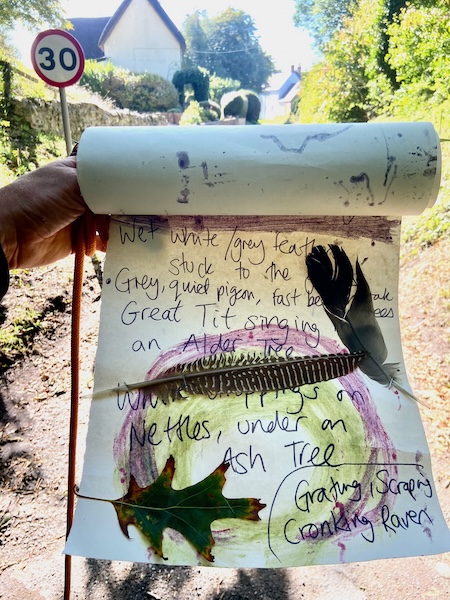

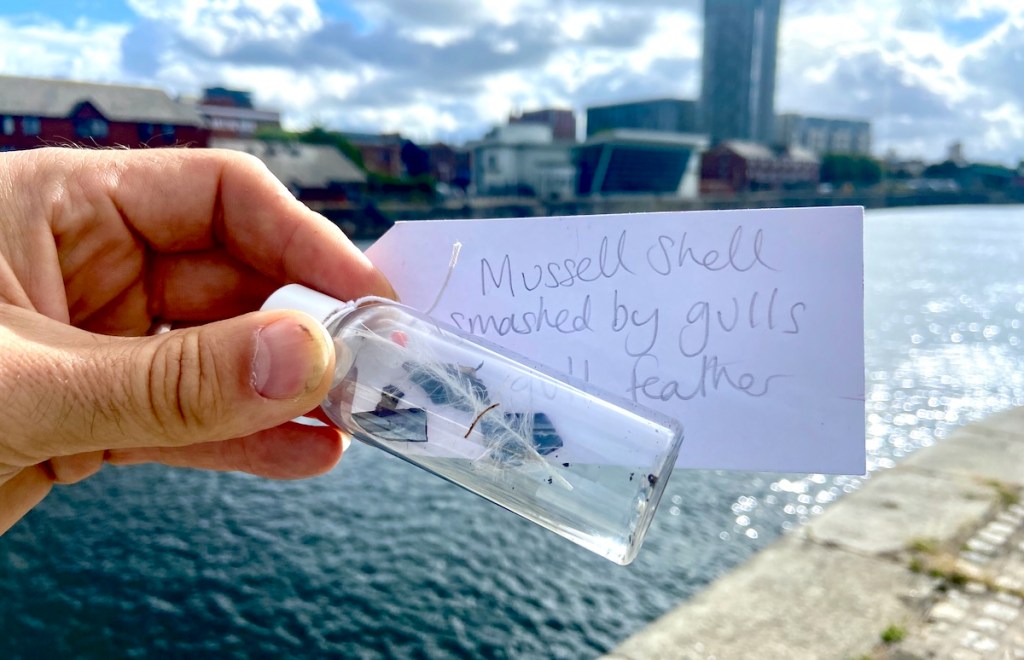

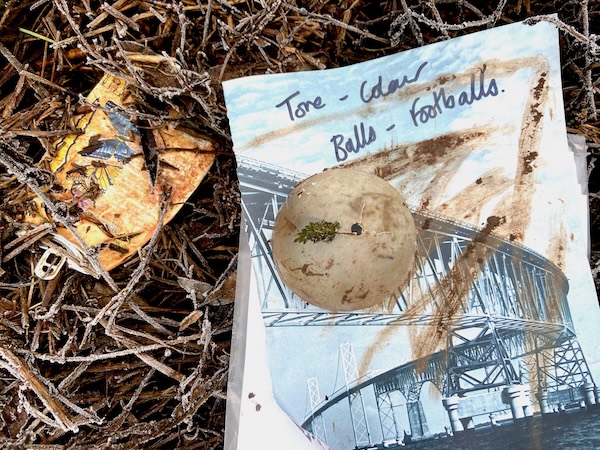

I often bring a way of recording the place and our conversation to these Queer River walks, and this time I brought us each a ‘pack of cards’, blank, torn pieces of white cartridge paper held in an old wage packet, on which to rub found pigments and make notes. I first started using this method back at art college in the early 1990s, partly influenced by the work of Herman de Vries, and sometimes buried them afterwards, before digging them up again weeks or months later, to see if the place had anything else to add.

They seemed appropriate in light of Lydia’s own work with walking, found pigments and multiples. Looking back, the wage packet also connected serendipitously with our conversations around artist’s pay. My cards now have a rough rectangle of colour on one side, and key words that I scribbled onto the other as we walked, just enough to remind me of our conversation.

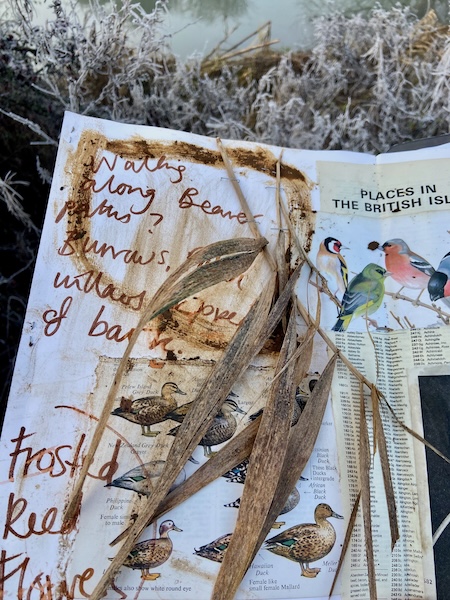

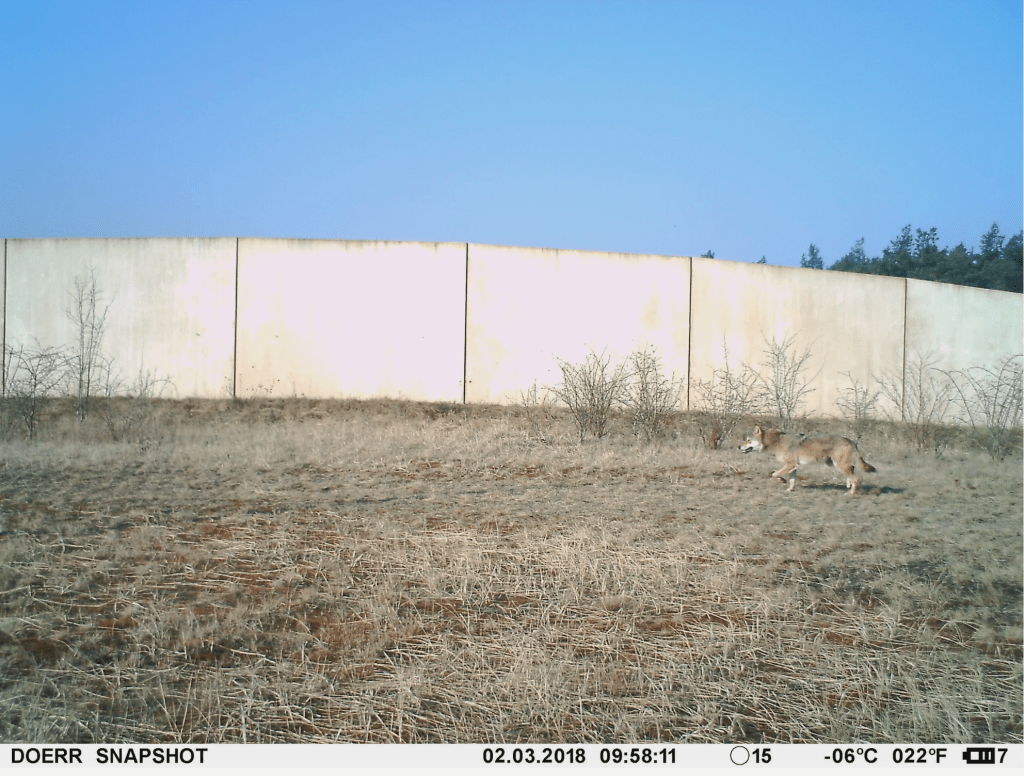

Our walk together took place on a dry day, along a path that was thick with mud after weeks of almost constant rain. I parked in the railway station car park, and a minute’s walk from my car, on the way to the Tithe Barn where we were meeting, I had already spotted some obvious signs of beavers. I hadn’t necessarily planned for beavers to feature in this walk, but I had been wondering just how active they were in the area. Walking on to meet Lydia and her dog Milo at the barn, we started off along the River Avon.

We were meeting at a time when my own PhD proposal (see more here) was very much on my mind (I’m currently rewriting it for another try at getting funding), and the day after I had watched two out of three episodes of the Dirty Business docudrama on Channel 4, a ‘shocking real-life drama of victims, whistleblowers and England’s water companies…’ The other thing that I couldn’t erase from my mind that morning, was a mental image from last Summer when I visited Bradford-on-Avon with family, peered into the river in the centre of town and saw a big pile of wet wipes and sanitary towels in the reeds. The water level had dropped, and the remains of the untreated sewage that previously been pouring directly into the river water, was now left high and dry.

We were walking out of town this time, and our conversation soon turned, as it has with every artist I’ve met recently, to the state of arts funding and artists pay in the UK right now, and the amount of unpaid work that is asked of artists in the form of open calls. There’s plenty online about this at the moment, including the huge number of applications organisations are receiving for each role advertised, so I’ll not go into depth on it here, only to say that with a number of articles I’ve read recently calling for artists and cultural workers to ‘stand up and take action ‘ in the face of the climate and biodiversity crises, the economic survival of artists who are trying to do exactly that needs to be addressed. The arts in schools have long been under attack, whilst whole departments have been axed within universities, and the ‘trickle down’ funding given to arts organisations just isn’t reaching artists on the ground.

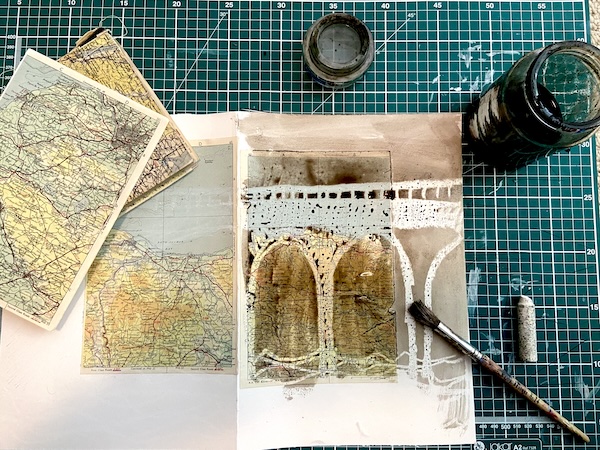

As we slipped and squelched along the footpath, we talked about flooding and sewage, and saw evidence of both caught up in tree branches along the river’s banks. Lydia dipped blotting paper into puddles and I rubbed leaves and different coloured soils onto my set of cards, whilst Milo seemed to be catching the scent of beavers.

Lydia has recently signed up to be a Water Guardian with We Are Avon, which will involve regularly testing her stretch of the river water. as part of an initiative covering the Avon bioregion. On a related note I’ll be working with Guardians of the River Itchen in Southampton in May to run a hands-on session for young people and their families, exploring the relationship between marine pollution and wildlife in the Itchen Estuary, building on my Pop-Up Studio residency with the John Hansard Gallery last year.

An aspect of Lydia’s practice that really interests me is the way she adapts her body and clothing to receive information from her environment:

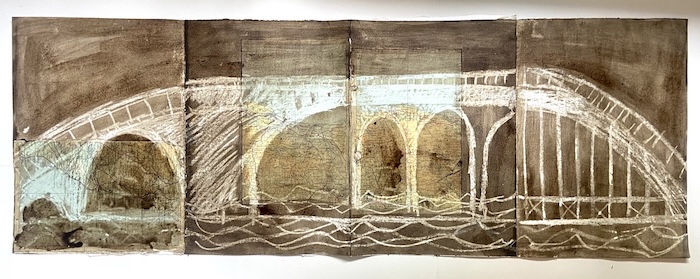

‘I use my body as a recording mechanism for my walks in a place, adapted walking boots capture the textures of the ground underfoot to become drypoint etchings printed with collected earth. Adapted gloves record the textures felt by my hands along the walk to become drypoint etchings printed with collected pigments. These form an archive of the textural surface as experienced on foot and by hand over time…’

I’ve long been interested in portable, interactive artworks that facilitate an engagement with place. My own experiments have leant more towards portable collections of objects, materials and information. These inform what I provide in the packs of resources I gift to participants on socially engaged walks, and the development of backpack-based interpretation, for example with Andover Trees United, for use by local people in engaging with the River Anton and its chalk stream tributaries.

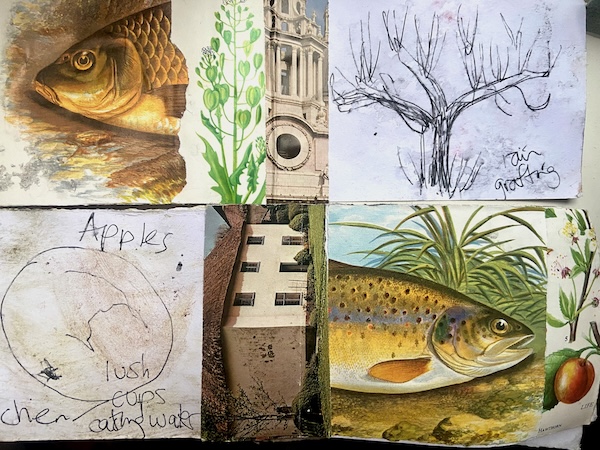

There are some obvious similarities between my and Lydia’s approach to making work, although the ‘end product’ can look quite different. We both make work that maps embodied experiences of places that are changing due to climate breakdown. Each of our practices values a slowness of engagement, and takes a closer look at the everyday detritus that is left behind on beaches and riverbanks, either by processes of erosion and decay, or the release of plastics into wetland ecosystems.

I also see a connection here between my recent Walking Pages that document a search for beavers, and record my sensory experience of the wider ecosystem, including litter and industrial waste, and Lydia’s Residues series:

‘Much of the work is made with ancient earth pigment Bideford Black as a way to hold a residue of materials discovered during walks. Many work with ghost nets foraged between the tides, and with experimental approaches to record the textures of each walk underfoot.’

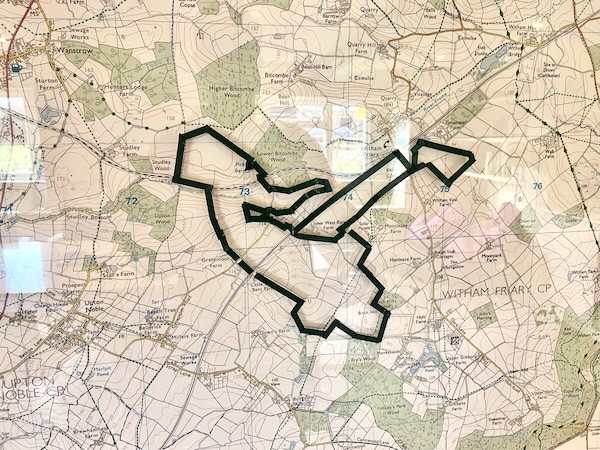

Now that I’ve walked here with Lydia, I’m planning to return soon and continue this series with Bradford’s beavers, building on last year’s walks along the Bristol Avon from Trowbridge and Chippenham (see Walking Out).

Mapping my embodied experience of beaver wetlands is a key part of my PhD proposal, and although not wanting to dominate the conversation, it was really useful for me to be able to air my frustration at the knots that I had tied myself in after countless edits. Lydia’s approach to using embodied approaches to receive knowledge from the ‘more than human’ world is very much aligned to my own, and I really appreciated hearing her perspectives on mapping and counter-mapping within practice-based research. from her experience with her own PhD.

Our conversation wove together other threads, relating to our children’s experiences of the UK education system and the relationship between beavers’ use of materials sustainably harvested from where they live and much human construction, where extraction may take place many miles away, with damaging impacts remaining unseen. We also wondered about the impact of digital media on a sense of place, especially when screen-based media can be used as a means of escape from the worsening state of the planet, divorced from the material and ecological reality, resulting in what Lydia described as ‘a creeping sense of placelessness’.

Thank you Lydia (and Milo) for your company. It feels more important than ever that artists and others exploring these issues come together to share experiences and support each other, as well as continuing to find joy in the green shoots of Spring and the beauty of what remains.

Lydia is currently showing work in the following exhibitions:

- Landscape – a Changed Environment: Messums West until March 9th

- Material and Maker: Gallery 57 until March 14th

- Hubert Coop and Friends – A Legacy of Art and Influence: The Burton at Bideford: until March 15th