Over the last few months I’ve been parking up and walking out from some of the towns and villages sited along the Bristol Avon and its tributaries, as they run through Wiltshire. Although the Salisbury or Hampshire Avon runs nearest to my home in the Vale of Pewsey, the two watersheds meet only a few miles away from here, with streams on ‘the other side’ feeding the Semington Brook and other Bristol Avon tributaries.

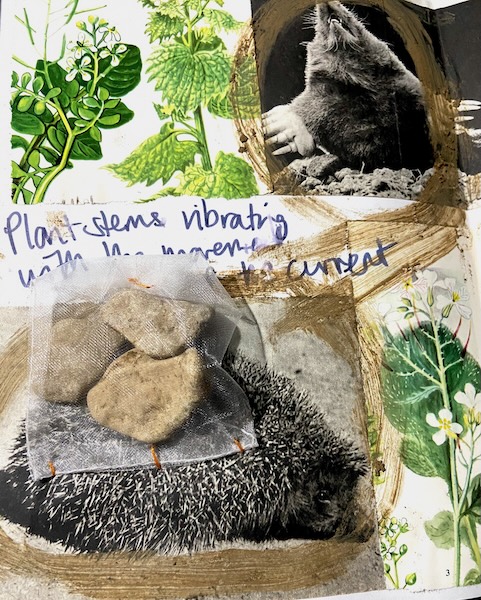

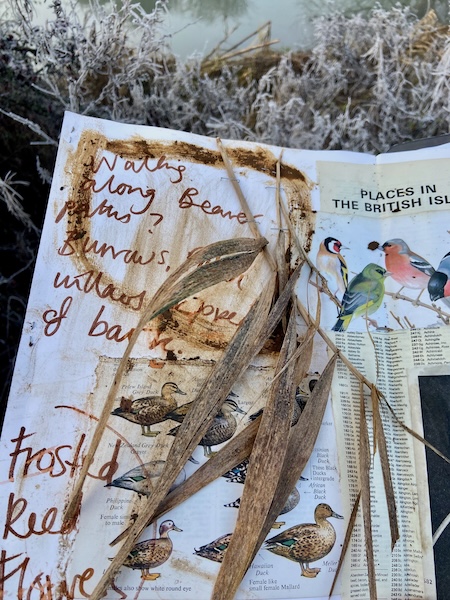

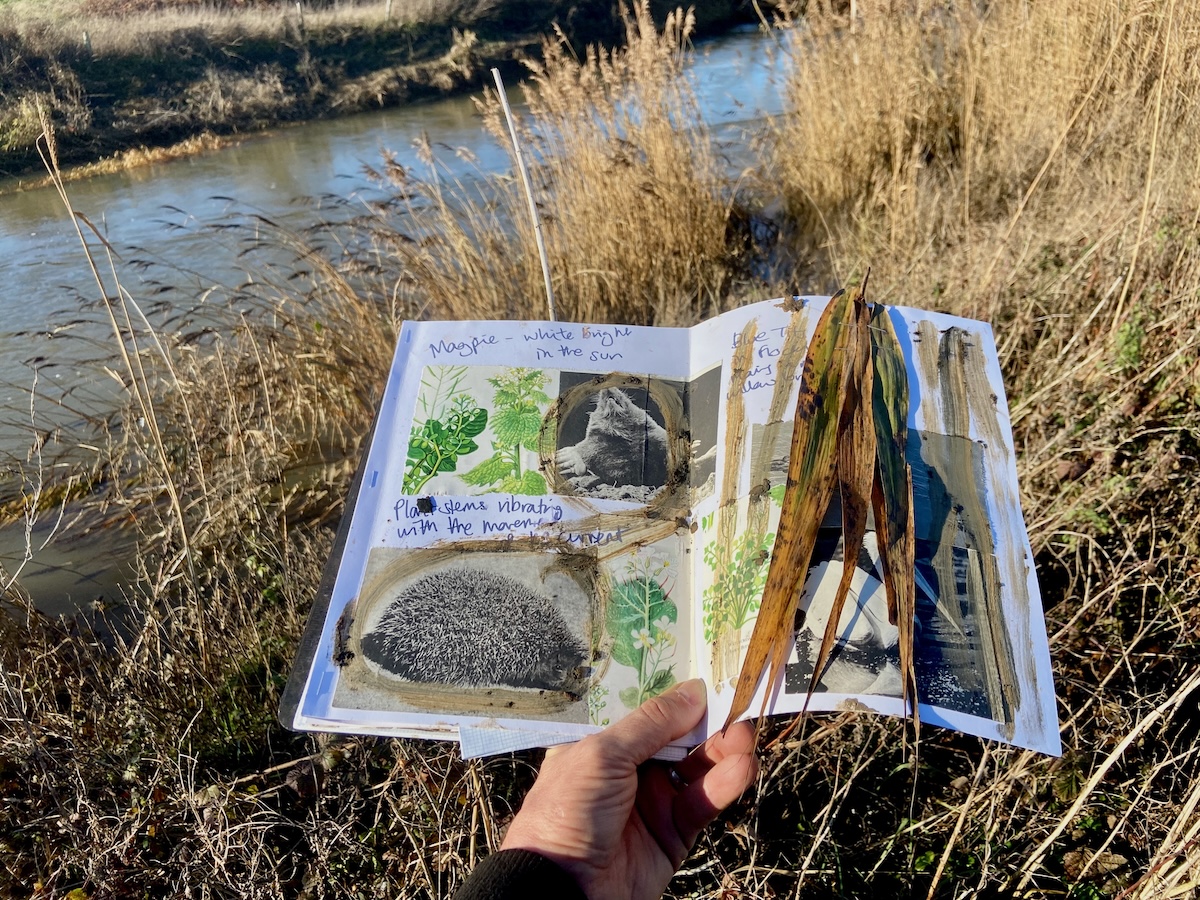

I’ve been using Walking Pages to document and process these walks. My Walking Pages vary, but generally consist of a series of paper pages that connect together in a linear way, recording what I notice as I walk. For these recent walks I’ve been using a fold-out concertina format, made up of six A4 white paper pages overlaid with collected botanical, architectural and other imagery that link to the subject matter of river wildlife and human infrastructure. Onto this surface I write, draw, make rubbings, and attach objects washed up by or left along the river, stapled in the moment or dried out and stitched on later in my home studio.

The printed illustrations, representing the idea of the ‘official’ British landscape, blend with the messy, multi-sensory and emotional responses that emerge in the moment, and what the river shows me. This includes a rough list of the mammal/bird species that I see, hear or notice tracks/signs of, and some of the plants too.

‘Noticing is my way of opposing a particular modernist practice of looking towards an imagined future. Certain things get coded as possible futures and then we develop blinders so that all we can see is our trajectory towards one kind of imagined future, which isn’t actually the future but is a stereotyped dream future. And so, we stopped seeing. Noticing is trying to take those blinders off to look at the world around us, with special attention to the more-than-human world, by which I mean the human plus non-human world…’

It’s quite an addictive process. Each walk informs my understanding of the character and health of a section of river, and provides a piece of the puzzle that I am building internally. The more I walk, the better I understand where I live, and that internal model builds. The two rivers connect everything together from chalk downland to railway embankments, agricultural land, towns and nature reserves, bringing life, providing blue/green corridors for the movement of plants and animals, and carrying our waste.

The OS Map App helps me find my way through industrial areas, farms and housing. The coloured dashes that indicate public footpaths and bridleways and which pass most closely to the wiggly blue lines of rivers and streams are the ones that I look for. When I’m a bit lost, a red arrow shows me how to get back on track. Awareness of our local river systems can be so limited and fragmented due to such limited access, so I’m using walking and making to piece together a multisensory, multi-species map using those parts that I can reach, and the Walking Pages are one element of that.

These walks are also helping me to develop my understanding of where beavers are living in Wiltshire, as I research human-beaver relationships, and beavers as makers. I log any signs I find of beavers as I walk, and upload my photographs to the Mammal Mapper App to contribute to county records. I also collect fragments of beaver chewed wood, to draw back in my studio, as a way of looking even more closely, or make scans of them to use later in artwork (video, installation etc).

‘Walking Out’ of town I walk out of a busy mind, out of the expectations of others, the need to mask or perform, and eventually out of the noise and busyness. I find it easier to notice the smaller, quieter details when there’s less people and cars; an otter’s head moving slightly as it chewed its catch near Chippenham for example, a glimpse of pale cream exposed wood amongst darker bark that shows me a beaver has had a chew on a waterside willow branch, or the piping sound of a Kingfisher signaling its arrival, flying low and fast above the water’s surface.

‘I have long thought of the outdoors as an escape, a distraction from everyday life. My safe space. It allows me to unload whatever’s clogging my mind, park it wherever I am, focus on something else… and then return to that original headspace with a clearer outlook. I’m refocusing my attention, yet resting my brain at the same time…’

I’m not looking to escape the urban experience all together though, just to bring my full attention to where I am and what I am experiencing. It’s not that a rural area is some kind of green oasis to escape to either, the rural spaces are often as heavily managed and affected by human activity as urban spaces. I can find myself in yellowed, sprayed fields, between chicken sheds or alongside solar farms, or anxiously weaving my way through farm buildings to find a gate or stile thet will get back to the river.

What I am primarily ‘Walking Out’ of then, are inherited ideas of the urban and rural, of what a river is and who lives there. What I’m ‘Walking Towards’ are direct experiences of the reality of that place, received through my body and my senses, and processed through making. The making of this kind of artwork acts as a mechanism for noticing and recording (in a similar way to my Walking Bundles). I do it to understand rivers as communities of life that weave the urban and rural together, experiencing which animals and plants live where, and the impact that different kinds of land-use have on the ability of a river community to live, grow and flow.

The return of Beavers to Wiltshire has provided me with a new way to think about and with rivers when I’m walking. Is there potential in that section of river for a family of beavers to re-make it to meet their needs? Can they create the space and habitat for the other species that their re-making supports, or is the river too constrained by farming, roads etc? And what happens when human and beaver infrastructure combine or collide?

‘Across Britain, rivers and streams have been heavily modified, with 85% of our rivers straightened, confined, or cut off from their floodplains. These changes have limited the ability of rivers to function naturally, contributing to increased flood and drought risk, declining water quality and the loss of biodiversity.’

Beaver Trust – Making Space for Water

We might expect these kinds of issues to be discussed by ecologists, environmental scientists, geographers, or maybe urban planners. Similarly if you mention environmental education, most people would think of science communication.

For too long art has been the ‘nice if you have time for it’ subject. Something decorative, something to make you feel good in your spare time. But arts practices developed in dialogue with places and communities, can provide us with sensitive ways to notice the reality of, and build new kinds of relationships with, the other beings with whom we share such places. Relationships vital to our ability to live well in a future impacted by climate breakdown.

I’ve been fascinated by and felt happiest alongside other animals since I was a small child. When I was growing up I had drawers full of shells, feathers, skulls and bones. I kept a folder on the wildlife that I had found in our garden. My favourite book as a small child was an Encyclopaedia of Animal Life, until I graduated on to The Amateur Naturalist by Gerald and Lee Durreell which helped me plan ant farms or owl pellet dissections. I kept injured birds and animals in the back garden or spare room and was always going to work with animals when I was older.

But the Secondary School career options, that offered an art or science route from school into University, couldn’t accommodate me and my creative, neurodivergent mind. So my planned Zoology degree turned into Fine Art instead, with as much time as I could spent outside the studio, in the woods and by the river, and a career of almost 30 years since, spent developing participatory methods to engage communities with their local natural and cultural heritage.

My arts practice now recognises and models the value of fusing art and science, and as a kind of hybrid Artist/Naturalist I provide ways of knowing places and ecosystems that use art and walking to go beyond the restrictive binaries and boundaries that divide art/science, urban/rural and human/nature, and blinker us to what else might be possible.

Bringing art and artists into dialogue with those working within river restoration, rewilding and other regenerative land practices, has the potential to support the development of new ways of knowing and being with wetlands, through creative mapping techniques and community engagement. Art practices can also be devised to include and learn from non-human animals (hence my beaver research), as practiced by many indigenous societies.

It may have taken me a while to see it, but looking back my career path created a role for myself that didn’t at first exist. My working processes as a practicing artist, and the sensitivity of my Neuroqueer body-mind allow me access to a complex, multi-faceted understanding of what we have come to call Nature, and our place within it, developed through direct experience, creative dialogue and collaboration, where sensory and cultural differences are valued for the insights that they can offer us all.

And I get to learn from beavers…

One thought on “Walking Out”