I’ve had a very rich and busy September. Working with groups and individuals in Liverpool with Up Projects, in Somerset with Hauser and Wirth and Spike Island, in Bath with Forest of Imagination, some really rich time in Portsmouth, beginning a ‘walking and talking’ mentoring process with artist Hannah Mae Buckingham. I’ve also started an exciting new advisory role with Not Bourne Yesterday: Chalk Stream Communities of the Chilterns (more to come on that soon).

Right now it’s time to slow down a little and settle into my home patch again, letting everything from these last few weeks settle, and decide where I’m heading next, in terms of focus/subject matter/media.

A couple of days ago on social media I came across an American 11 year old boy called Samuel Henderson, who can do amazing bird impressions (impressions doesn’t seem the right word somehow, he embodies them through sound), and is also autistic. I was blown away by his skills, and set thinking by an instagram post that said what an amazing hunter he would have been 150 years ago. Why a hunter? What other benefits come from inter-species communication? What about the wider value of learning from and connecting with our non-human kin?

As well as connecting with my Neuroqueer Ecologies research, he made me think of Irish sound recordist and ornithologist Sean Ronayne, who went on a mission to record all of the native birds of Ireland, and who is also autistic. There’s an interview with Sean here where he talks about the relationship between sound sensitivity and autism, and a starling that learned to mimic his voice and Cork accent, amongst other things.

‘…I’m seventy, up to ninety percent tuned into the frequency of the natural world, my ears are scanning. And when I’m having a conversation… my attention is only partially yours. If anything else speaks up, a bird or whatever, I’m gone.’

Sean Ronayne

When I first set up Queer River I was thinking about what queerness brings to an awareness of ecosystems, and since then have brought neuroqueer experiences into the mix too. When first exploring LGBTQAI+ people’s experiences of green and blue spaces, I was partly looking at the impact that trauma plays. For instance, one article (the reference is lost from my memory sadly) mentioned the possibility that the hyper-vigilance that a queer person might experience in certain settings, due to traumatic previous experiences or a more general awareness of the risk of being openly queer, could also lend itself to a hyper-awareness of birdsong.

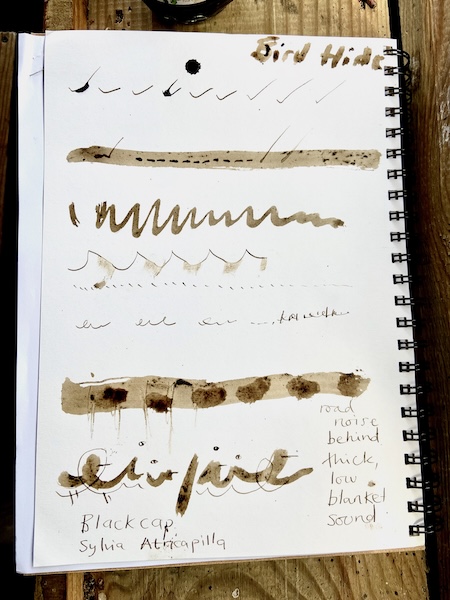

In previous work with organisations (e.g. a project/course for Well City Salisbury (WCS) and Wiltshire Wildlife Trust, images below) I have supported participants to use visual ways to document their experiences of birdsong, partly inspired by spectrograms. I also produced an activity resource on a similar theme for WCS. Over the years I’ve researched Great Bustard reintroduction, the place of Swans in popular culture, and the work of artists and composers (e.g. Marcus Coates and Stevie Wishart) that have been inspired by and collaborated with birds.

What I’m interested in now, is the relationship between autism (and neurodivergence more generally) and birds/birdsong. As well as Samuel and Sean, well known autistic naturalists such as Chris Packham and Dara McAnulty, (author of Diary of a Young Naturalist), are also drawn to birds. Do we all share something? What relationship do sensory and processing differences have with a sensitivity towards/appreciation of birdsong?

‘I was studying badgers and kestrels… my life was pretty polarised between punk rock and birds. I became very solitary… I was very confused and angry, principally with myself, because I didn’t understand why I was different from other people and I couldn’t see that difference. To ourselves, we all feel normal. At that point, I was trying not to communicate with anyone. My mission was to get my degree, do a PhD and spend the rest of my life hiding in an ivory tower studying birds…’

My Younger Self Would be My Biggest Critic, Chris Packham

Joe Harkness has recently released the book ‘Neurodivergent by Nature, published by Bloomsbury. Joe’s book is a follow up to his first book Bird Therapy, which drew from ‘...his personal experiences with mental health challenges, Joe discovered solace and resilience in the natural world, particularly through bird watching.’ Joe and I were going to meet as part of his research for the new book but that didn’t quite happen in time. I’ll be reading it soon though.

‘After receiving an ADHD diagnosis in his thirties, Joe Harkness began to question whether his bond with nature was intrinsic to his neurodivergence or something developed through his life choices. Keen to know more, he connected with other neurodivergent people who share his passion for the natural world. Threading their stories with his own, Joe explores why they chose to seek diagnosis, the ways they find solace and understanding through nature, and what led many of them into nature-related careers.’

Exploring the connections between nature and neurodiversity, Bloomsbury

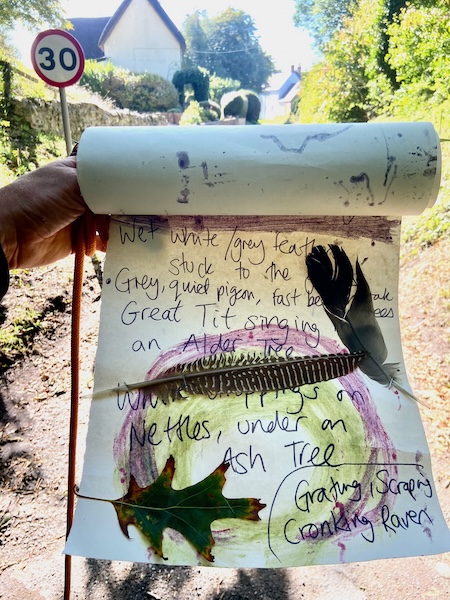

As usual, my initial research uncovered more questions than answers, and with an already slightly overloaded brain after a busy few weeks, I decided to get out of my head and out of the house. So I went on a walk, with a long blank roll of paper, a black pen and a stapler. As I asked a question of the children that I collaborated with at Forest of Imagination in Bath – ‘Where does a river begin?’ – so I asked myself a question on this walk – ‘How do I notice birds?’ – trying to become more conscious of how I become aware of birds, and the role that my different senses play.

As I walked out of my house and on a loop that took in the River Avon, country lanes and sheep fields, I wrote down each bird I noticed and how/where I’d noticed it. Seeing a Kestrel perched on a telegraph pole, hearing the calls of a family of Red Kites that nest nearby, seeing/feeling the shadows of unknown birds passing over the tarmac in front of me, picking up a grey, loosely banded Woodpigeon feather.

I noticed chains of reaction as a Kestrel spooked a group of Jackdaws that flew across the sky, flushing a Magpie which then rose up out of the hedge, pushing the by now perching Kestrel off of its perch, up to where my eyes connected with a Red Kite in the distance, coming to see what food a tractor cutting silage had exposed.

As I walked, I thought about how in the moulting season I had gathered quite a few feathers from birds of prey, and that had became the most noticeable bird presence. If I’m collecting objects then I’m more likely to notice feathers, whereas if I’m filming or have my sound recorder with me then I pay more attention to closer, bigger, more ‘filmable’ birds such as swans, or bird song and sounds. When I was in the New Forest looking for evidence of the animals that lived there as part of my Neuro/Queering Nature residency with Spud, I was paying more attention to footprints, and whoever had recorded themselves on my camera trap.

Ultimately though, in my arts practice I tend to draw on all my senses and piece together a more holistic ‘picture’ of my environment through their interconnection. I’m less likely to prioritise one sense than another. Walking and telling myself to only notice birds was hard, it started to make me feel tight and tense, which wasn’t the idea of going for a walk at all. The huge amounts of shiny acorns on the floor, the changing colours of the leaves, sheep wool on the fence, all called for my attention. In the end I cut myself some slack and started adding a little colour between the rows, smearing the last of the year’s blackberries, rubbing on fresh green grass and some mud exposed by the scraping of deer hooves. For me the birds don’t exist in isolation, everything is interwoven.

The usual benefit to me of going on a walk, especially after a busy time of designing and holding spaces for others, is surrendering to the place and what it wants to show me. It’s a chance to let go of the need to focus my attention and meet others’ expectations, and to allow my boundaries to dissolve. Trying to only notice birds didn’t quite fit with that, even though it was my own agenda.

‘I think there are multiple effects that nature has on me. First of all, it gives me a place that has no judgement in it; a robin is not going to turn around and tell me, ‘What you’re doing is stupid’. And that sort of freedom in a place where I can just go, and I know that there’s going to be no backlash from it, that I can just relax, and from that it gives me a sort of base grounding point from which I hold an anchor myself in my life.

Every time I go out into the forest, I gain almost new layers and old ones are taken away as I go over falls. And this I think is one of the most important things that I found in nature, that when you’re in it you can sort of go into your thought processes in your mind, and pick the problems and the areas that are going wrong and fix them. And there are no distractions that you find from the real world, that will divert you from this course. It’s just you, nature, and your own mind…’

In Conversation with Dara McAnulty, Dara McAnulty

One of the reasons I didn’t originally think that I could be autistic was that I didn’t fit the usual idea of what being autistic looks like, and I am intrigued by the fact that I still don’t feel like I fit. My noticing of birds isn’t like Samuel’s or Sean’s. But my need to get outside and be with non-human animals is. The benefits sound very similar. So perhaps what we share is the need to decompress after consciously editing and masking ourselves to navigate social spaces, and the sensory sensitivity, and hyper-empathy, that enhances our awareness of other animals and our entangled relationships with them.

Research shows that many autistic people have experienced trauma, from bullying, harassment or abuse, or from the constant grind of trying to navigate social systems that don’t cater for our needs. All of the people I’ve mentioned above have described the therapeutic value of time spent ‘in nature’ (in a less human dominated world, where other voices can be heard).

”Belonging’ conveys the experience of becoming whole through integration of all aspects of ourselves, including the shadow aspects we conventionally suppress. Time with the wild non-human world can support us to do this, as we re-experience ourselves as part of our entangled universe. This can be particularly true for autistic people. Time away from humans provides the rare possibility of being able to fully unmask, allowing complete sensory immersion and self-integration.’

Belonging (March 2023), Kristen Lindop (image above)

We are different to each other, as all autistic people are different, but we all benefit from time spent outdoors, outside of busy urban environments, opened up to the communication of the more than human world. Aided by our sensory sensitivities, that in other environments can cause distress and discomfort.

But why birds in particular? I don’t know about that yet, but I’m aware that the majority of examples I’ve used above are white, male-presenting people (apart from Artist Kristen Lindop), and that birdwatching and the spaces associated with it can be very white, male spaces. The practices of keeping a bird list in birdwatching also echoes the urge to collect that I mentioned above, that some autistic people experience. With Sean there also seems to be something about collecting the calls of all Irish native birds (see my earlier post on autism and collecting here).

I only recognised myself as autistic when I started to look at and hear from a wider range of autistic experiences, particularly women and gender non-conforming people, and I’d be keen to hear from women, trans/non-binary and Black neurodivergent people on their experiences of birds/birdsong and birdwatching.

‘I experience strong physical and emotional responses to many presences, particularly birdlife… Being with, and becoming with, birdlife is a powerful multilayered experience for me – in my art practice and in my life in general’

Artist Kristen Lindop (via instagram)

Please do comment or email if you have thoughts or experiences that you’d be happy to share. In the meantime I’ll leave you with a short video clip of a hunting Kestrel from near the end of my walk…

NB. I’m aware of scientific research carried out comparing bird and human brains, deliberately impairing the ability of birds (e.g. captive Zebra Finches) to sing, in an attempt to understand what might cause some autistic people to be non-speaking. I have chosen not to go into that in depth here.

One thought on “How do I notice birds?”