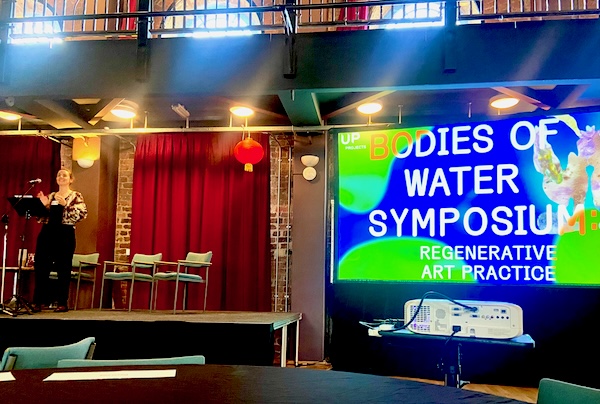

On Thursday I led a walk in Liverpool titled Neuroqueer Ecologies: Noticing Differently, as part of the UP Projects symposium Bodies of Water: Regenerative Art Practice. The symposium was curated by Justine Boussard (below, left) and partnered with the Liverpool Biennial, with an associated public art commission by Anne Duk Hee Jordan at A la Ronde in Exmouth and Haigh Hall in Wigan.

Before I left Liverpool on Friday I also managed to get around a few of the Biennial venues, visiting work by artists that connect with my practice, curated this year by Marie-Anne McQuay.

It’s only the third time I’ve been to Liverpool, and the last time was about 30 years ago, so I write this as a visitor, sharing a sample of what most connected with me and will feed into my Queer River research.

My walk aimed to offer a taste of the methodology that I most use within Queer River – walking, talking and making with rivers; noticing how water moves/is moved through the city, and following it down towards the docks. I wanted to highlight the insights that neurodivergent perspectives on ecosystems can offer, and bring the subject of watery, regenerative practice into a real world setting, through an embodied experience.

At the start of the walk I shared the following quote from autistic Philosopher Robert Chapman:

‘A radical politics of neurodivergent conservation is also consistent with a radical politics of environmental conservation. After all, it has been the same logics, the same system, that has ravaged the biodiversity of the planet as has sought to eliminate the neurological diversity of humanity…’

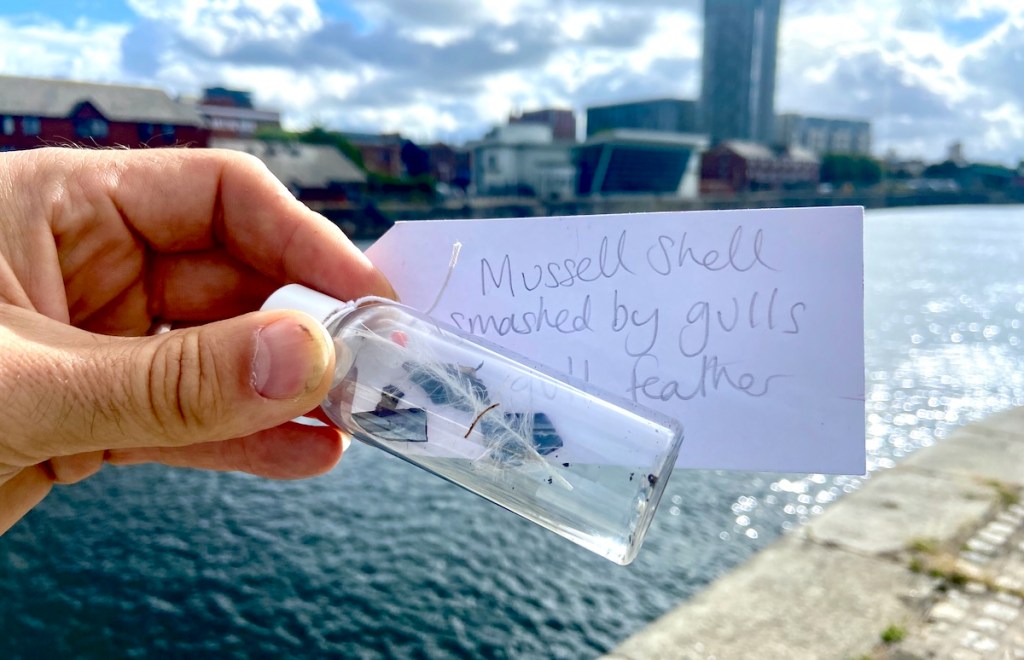

I gave each person a pack of resources to document what they noticed (a blank paper map, pencil, crayon, empty bottle, envelope), and I carried another bag of equipment (stethoscopes, magnifying glasses etc) for us to share.

Before going to Liverpool I had started to look into the history of the River Mersey and its place within the city’s culture. It was almost exactly 4 years to the day that I had arrived in Glasgow for Queer River Wet Land. There I was working with the University ahead of Cop26, to reflect on and walk with the Kelvin and the Clyde, learning about their industrial heritage and potential future flooding, and thinking with others about whose voices are heard in discussions on climate breakdown and river futures, and whose voices are missing. Similar thoughts were going through my mind about The Mersey.

I first discovered that the Mersey is thought to take its name from its place as a boundary between Mercia and Northumberland (and more recently between Lancashire and Cheshire), but that possible earlier Celtic origins link the modern name of Mersey with Meteia, meaning ‘the reaping one’ or ‘she that cuts down.’

Also, I was aware of the role of slavery within Liverpool’s history as a port city, although less familiar with that history than with towns and cities nearer to my home in Wiltshire (see an earlier post here).

‘Liverpool ships were responsible for the transportation of over 1.1 million enslaved African people to the Americas between 1750 and 1807, more than any other British port. Written histories of the town begin to appear in the midst of Liverpool’s rise to prominence in the ‘African trade’, at the end of the eighteenth century. Liverpool reached its slave-trading apogee during the decade of legal abolition at the very beginning of the nineteenth century, when the town owned close to 80 per cent of Britain’s total slave trade.‘

Liverpool’s local tints: drowning memory and

“maritimizing” slavery in a seaport city

As a white person, and a Dad to a teenage boy of Jamaican heritage, I’m keen to advance my learning on the place of slavery within British history, and of racial justice within environmental/climate issues. My knowledge of climate justice draws on the experiences of different communities, including recent work with Disability Arts Online, on behalf of Climate Museum UK, to providing professional development on the relationship between disability justice and climate justice.

One of the things that stood out whilst digging around online, was a quote from a speech by Michael Heseltine in 1981, written whilst staying in the Atlantic Hotel, and ‘standing with a glass of wine’ overlooking the Mersey. Heseltine was in Liverpool following The Uprising of Liverpool 8 (aka the Toxteth Riots):

“The Mersey got to me. It was enormously significant in the history of our country, and I felt a debt to that river…It was an open sewer, and I felt deeply sad that we hadn’t realised what an enormous, valuable resource it was. That was where the idea came from, that we must make good the degradation of centuries.”

Heseltine’s ‘It Took a Riot’ speech led to the development of the Mersey Basin Campaign: ‘established in 1985, with government backing and a 25 year lifespan, to address the problems of water quality and associated landward dereliction on the Mersey and its tributaries..’. The MBC worked with local people to improve water quality and encourage ‘sustainable waterside regeneration’. Their work is now continued by the Mersey Rivers Trust.

The cleaning up of the Mersey was obviously a very good thing. In 2002 oxygen levels were reported as being able to support fish along the entire length of the river for the first time in recent history, after years of pollution by sewage and industry. Salmon returned, and occasional grey seals, porpoises and dolphins visited (sadly today the Mersey has one of the highest loads of ‘forever chemicals in the world). A Conservative minister being praised as the saviour of the Mersey however, at a time when poor housing, environmental pollution, high unemployment and institutional racism within the police, had led to the disturbances that brought him to Liverpool, seems pretty simplistic.

‘Heseltine’s correspondence itself indicates that the release of details of the new arrangements for Liverpool’s regeneration should not be released until he had returned from holiday, stressing that ‘he does not want the statement to go out while he is lying on a beach in Mauritius. He thinks the reaction would be unfavourable’.

The Thatcher government’s economic and social policies played a key role in the decline of British industries and communities in the 1980s and 1990s, just as austerity and Brexit have in recent years, and Douglas Howe then Chancellor of the Exchequer, was quoted as suggesting a ‘managed decline’ of the city. The uprisings in Liverpool and in Brixton (and several other major cities) led to the commissioning of the Scarman Report, which highlighted the need for policing reform and improvements in housing, and identified ‘racial disadvantage’ as a key factor in the disturbances. The Scarman Report also informed the development of the Race Relations Act in 2000.

A Liverpool University survey undertaken 5 years before the Toxteth riots revealed that 31% of local employers admitted to acting in a discriminatory way to black applicants…’

The approach taken to regeneration in the Toxteth area included compulsory purchase and demolition of housing (including social housing), with associated impacts on local communities. A campaign was eventually set up to save the ‘Last 4 Streets’, leading to the creation of Granby 4 Streets LCT in 2011, who went on with Assemble to win The Turner Prize in 2015:

‘After the riots in 1981, the streets of Toxteth in inner-city Liverpool went into decline and its housing, services and residents suffered with it. The situation was compounded by a series of failed regeneration plans, leaving the streets drained of life. After 30 years of neglect, the local community decided to take action; they started cleaning, planting and painting their streets and over 100 boarded up terraced houses in them. They set up a vibrant monthly market and they campaigned to stop the demolition of the last four remaining original streets.’

As we walked from Black-E on Thursday (our base for the symposium), down to Queen’s Dock, all of this was in the back of my mind; the relationship between regenerative practice in public art, the restoration of wetland ecosystems, and the regeneration of post industrial/urban areas, where economics, politics and racial justice all come into play.

The creation of the city of Liverpool involved building over large sections of the Mersey watershed and its associated ecosystems, as well as creating a hard edge along the main Mersey channel. Building over what originally would have been a network of smaller waterways, and creating large areas of hard surfacing, both increases flood risk, and denies space for plants and other animals to live.

‘Liverpool is the forth highest risk in the country for surface water flooding. This is a result of urbanisation, aging infrastructure and that a large percentage of water courses are culverted which leads to standing water. Because of climate change, both the chance and consequence of flooding has increased.’

On our walk we noticed mosses and Buddleia sprouting from older brick buildings, and a small artificial island in the Wapping Dock that had provided a place for a family of Canade Geese to nest. Buddleia often appears in urban areas, sprouting out of cracks in walls and pavements. The botanist Mark Spencer, with whom I walked for Queer River in 2021, described how Buddleia is planted to attract butterflies, and readily spreads along connecting structures such as roads, railways and rivers, but that no studies had been carried out on its impact on butterflies. They readily feed on its nectar, but its leaves don’t offer food to caterpillars, and it may actually out-compete those plants that do.

I was excited to see that Liverpool Biennial artist Kara Chin had included modelled mutant Buddleia plants within her installation Mapping the Wasteland: PAY AND DISAPLAY (above right) at FACT Liverpool this year. The text alongside reads ‘The Buddleia plant was first brought to the UK from China in the 1890s…Chin draws comparisons between Buddleia’s status as an ‘invasive’ species and the racist language used in mainstream media about immigrant populations’.

My recent work with young people at the John Hansard Gallery in Southampton, another port city, responded to the work of Palestinian Artist Alaa Abu Asad who similarly explores cultural responses to the spread of invasive Japanese Knotweed, as a metaphor for racist and xenophobic language used in relationship to human migration.

My own research has started to look at whether reintroduced native wetland species such as beavers can be said to bring an indigenous perspective to river restoration (re-making) in the UK, and what multi-species collaborations can offer us. What could I as an artist learn from being apprenticed to beavers?

The morning after the symposium I continued exploring the waterside, via a walk to Open Eye Gallery and Tate Liverpool, to meet the artist Helen Kilbride. As I wandered along, surrounded by smooth, pale, engineered stone surfaces, contrasting with the crumbling brick of the day before, I wondered how far back into the current city the waters of the Mersey would have reached. What liminal places would have existed here before where land and water met – marsh, salt marsh, reedbed? What other rivers and streams would have joined the Mersey that are now filled in or culverted?

‘Beacon Gutter once marked the boundary between Liverpool and Kirkdale; as of 2025, it’s been buried for 200 years. Dingle is named after the brook of the same name, which flowed down Park Road. Over 15 miles of buried waterways exist in Liverpool. Today, the Mersey may be the only river most people think of in Liverpool, yet across the city run the Alt, the Jordan, the Old Garston River and others.’

Streams of Consciousness: In Search of Liverpool’s Lost Rivers, Robin Brown

At Tate I took a photograph of an indigo-dyed textile map of the city, accompanied by a soundtrack, created by Antonio Jose Guzman and Iva Jankovic (below left, followed up later with a visit to their installation at the Walker Art Gallery, below middle and right).

‘Guzman and Jankovic reinterpret the history of sacred indigo textiles, which are deeply connected with colonial histories and the trade of enslaved Africans who carried the expertise of cultivating indigo with them to the Americas. The textiles feature an abstract pattern of intercultural DNA sequences that embody a global connection between the Black Atlantic…The accompanying soundscape alludes to ideas of belonging and exclusion through an exploration of diasporic sounds that combine electronic music, dub, punk, and Senegalese drums’

From the Tate I walked to FACT, and from FACT to Bluecoat, where ChihChung Chang‘s installation combined rubbings of manhole covers and other urban infrastructure in the shape of a Chinese arch (I had used the same technique on our walk the day before). Chang’s arch was combined with a handmade boat and projection of archive imagery, referencing ‘rapid-changing and evolving environments such as ships, islands, water and ports’.

Also at Bluecoat, was Odur Ronald’s installation Muly ‘Ate Limu/All in One Boat, made from aluminium printing plates and scrap metal:

‘The jerry cans reference the dangerous and illegal methods people sometimes use to cross seas to Europe…The arrangement of the installation references The Brooks – a renowned ship which travelled the passage from Liverpool via the West Coast of Africa, carrying over 5000 enslaved people…’

My last stop of the morning, before I travelled back to Wiltshire was the Walker Art Gallery where I came across the work of Leasho Johnson. Johnson is a Queer artist of Jamaican origin who ‘aims to disrupt perceptions around historical, political, stereotypical and biological expectations of the Black queer body.’

I realise that as a white person, I am learning about Black experience of rivers and other waterbodies from the outside, piecing a picture together through the voices and artwork of others. This post is intended as a way to publicly process and document my thinking, rather than make myself out to be some kind of expert. I’m keen to hear from others with related experiences if you’re happy to share them with me, and am particularly interested in the Black community’s relationship with the River Mersey in the present, and other Black artists/writers exploring wetlands through their work more broadly.

Thank you to Justine and UP Projects for inviting me to Liverpool to walk with The Mersey, and to everyone who joined us on the walk. And to artist friend Alys Scott-Hawkins who was my hotel breakfast buddy, and provided some of these photos of the walk, as did Lucy Caruthers, designer of spaces and experiences.

I’ve really enjoyed seeing people’s images and reflections from the walk being shared on social media, and feel happy to have created a space where people felt able to take part and record their experiences in a way that worked for them. Please do stay in touch if you’d like to, I’d love to hear from you.

2 thoughts on “A Taste of the Mersey: Racial Justice and Regeneration”