My work ‘out there’ (outside of my home and studio) now quietens for the Summer. I have some lovely one day events and CPD sessions I’m facilitating in August, but apart from that, life can slow down for a bit. When I am doing my work with organisations and communities I need to interpret my practice and working processes for them. I compartmentalise, and focus on specific areas and aspects that relate to that particular audience. But Queer River, although it informs and encompasses much of this work, goes beyond this segmentation. It flows where it needs to go, connecting areas that need to be connected.

I’ve recorded some really interesting conversations over the last year for different podcasts, and there’s a new one being published very soon on the About Time podcast with Chris Nichols. In it, as with most work-related conversations, Chris asks me to talk about what I do, what Queer River is, and why I have come to specialise in working with rivers and their associated communities. I can’t remember my exact answer to Chris, but I talk about my relationship with rivers as a subject, how I have always felt drawn to watery places, and been a keen amateur naturalist, I realised this morning however, that the key reason I work with rivers is because I have a Rivery Mind.

My mind flows from subject to subject, across disciplines and contexts. I think here about research from Rachel Clive about the relationship between geodiversity, neurodiversity and Freedom Space for Rivers:

‘…neurodivergent behaviours, like different river behaviours, are not defects or problems to be controlled, disciplined or eradicated, but are natural differences which engage in processes that can self-regulate, that can nurture new life, that can suggest different ways of doing things that are valuable to all, whether neurodivergent or not.’

This flowing of my mind is both Neuroqueer and Neuroqueering, it goes where it needs to go and it brings its own perspective on the world. It is wide open and hyper sensitive to sensory information and the feelings of others. Compartmentalising can be both for the benefit of others (i.e narrowing my thinking to make it easier for others to understand), and for my own employability and wellbeing (making myself safe or acceptable and more obviously relevant for people who tend to cluster their thoughts into specific areas). But what rivers give me is a model of how to be fully myself, and a dynamic structure which can hold the complexity and allow the fluidity of my practice-led research. Thinking with rivers suits my river-y mind.

This isn’t what I was going to write about today. What I was going to say is that now I have the time and space to allow my mind to not need to know what it is doing or where it is going , I can relax into walking and making, and go on a deep dive into whatever takes my fancy. And that subject that takes my fancy right now is Bridges.

Recently, I’ve been walking and cycling from my home in Wiltshire to bridges that cross the Hampshire Avon. Staying local and renewing my relationship with my home river is grounding after a busy few months of travelling and translating my ways for others. I didn’t have a specific reason for visiting bridges other than a feeling that they had something important to say, something to teach me about our relationship with rivers, and the rest of what we’ve come to call ‘Nature’. Something about power and relationship perhaps. Bridging is generally thought of a positive thing, bridging differences between communities for instance, but there’s more to it than that, and as Queering and Neuroqueering both act to blur and sit across conceptual divides, I had a feeling there might be an interesting conversation to be had about/with bridges.

This post shares the start of that conversation with bridges, and ties in directly with my work on Neuroqueer Ecologies (a term I coined a couple of years ago and a thread that weaves itself through my Queer River work). In it I deliberately let my thoughts flow, rather than overly edit and translate, as a bit of an experiment.

I don’t know how your mind works, or how much you’ll get from me sharing this current set of insights from my Rivery Mind, but it feels important to be open about how I work behind the scenes. Before I turn up ready to talk about chalk streams or lead a workshop on noticing and recording biodiversity through art, I go through a whole research process, and then then translate my knowledge and understanding from river minded-ness into something more accessible to the general public. Of course I recognise that many others I work with are neurodivergent too, and that my work is much more about dialogue than a transmission of ideas, but in a sense I am bridging worlds for the benefit of participants and commissioning organisations. It’s work I love, but it can also take a lot out of me, so remembering the value of getting back into the flow is vital.

On one of my recent bike rides in the Vale of Pewsey (something I touched on briefly in my earlier Queer River research), a chalk valley shaped by the headwaters of the Hampshire Avon, I started looking more closely at bridges. It reminded me that when I started Queer River, my plan was to walk its length with invited others. But I soon realised that access to the river is very limited, with much of the land alongside it in private ownership, and that bridges often offer the only form of access.

Looking over the edge of a road bridge into a river, especially with cars whizzing by, can make me feel unsafe and like I’m not meant to be there. Looking through or over barriers, I feel cut off from the river below, like watching an animal through the wire at the zoo. I’m raised up, set back and only get a tiny glimpse of a dynamic community of life. Looking down onto ‘Nature’, emphasises the cultural separation.

Of course, humans aren’t the only animals to use bridges. The underside of human-made bridges are often used by otters to mark territory with their spraint (the slightly fishy, jasmine-tea scented droppings they leave on rocks and bridge foundation stones.) I’ve been reading some research on how otters on my local river, and how they’ve been eating invasive American Signal Crayfish, the shells of which then turn their spraint pink. I have added a photo of said pink poo below. Not a great quality image I know, but it was taken while crawling under a low, dark bridge. If the otters can’t find a way to pass under a bridge via land, they often opt to cross the road instead, leading to road deaths and forming an barrier to otter populations returning to historic habitat (see here re the installation of a ‘mammal shelf’ under a bridge in Sussex).

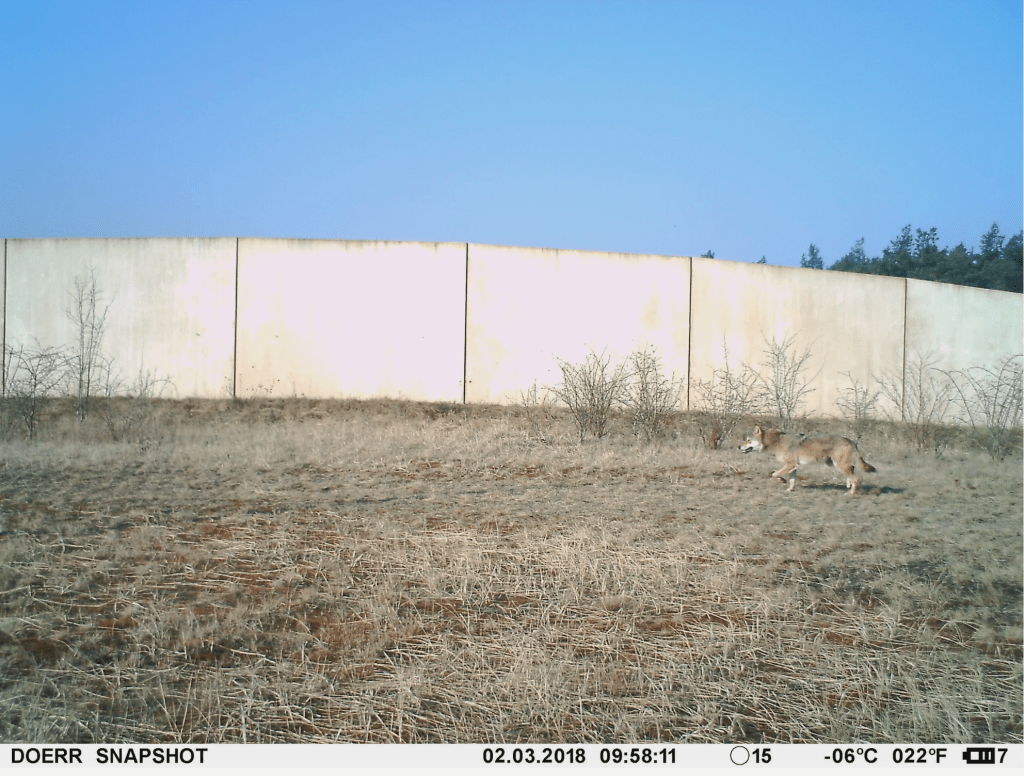

While we are talking about multi-species interactions and bridges, I’m reminded that bridges aren’t always made for people to cross (see here for an article on wolves using a Green Bridge in Germany, images also below), or indeed made by people. Archaeologist Bryony Coles in her work on Doggerland, has suggested that humans were likely to have used dams made by Eurasian Beavers as bridges across wetlands.

Coles also carried out research on the Somerset Levels, into the building of the Sweettrack in the Brue Valley and other wetland trackways built from wooden stakes. When researching the cut marks on these stakes, it was realised that some weren’t make by flint tools, but by beaver teeth. The humans were gathering beaver chewed lengths of wood and repurposing them to create their raised walkways, perhaps even gathering them from the beaver dams themselves. Taking from one kind of bridge to make another (the stakes would have been similar to this one I found photographed below).

It makes sense to me that humans have used beaver dams as bridges and trackways in the past, and that they learned some of their techniques from beavers, through living side by side. Youtube has some gorgeous videos (example below) of camera trap footage, showing different animals using such dams to cross boggy ground in the US and Canada. Human animals surely would have done the same thing in the UK in the past.

The simplest form of bridge of course is a fallen tree, which different animals use to cross a stream or river, avoiding getting cold and wet, or eaten by aquatic predators. Research in Poland (see here), has showed that larger mammals tend to prefer fallen trees, while small mammals preferred the interconnected wood and earth structures created by beavers. The researchers suggest that as small mammals can walk through the spaces created between the branches, they may gain protection from aerial predators.

I’ve added a short clip below of a beaver dam that I recorded during a visit to the Norfolk Rivers Trust beaver reintroduction site on the River Glaven, and a photo near the end of the post of a fallen tree bridging a local tributary of the Avon near my home in Wiltshire. I plan to get a camera trap up near one of these tree bridges soon.

In September, I’m going to be leading two interactive walks. The first, with curator Justine Boussard for Up Projects in Liverpool, will draw on my Neuroqueer Ecologies research and Queer River methodologies to accompany delegates from the Bodies of Water symposium to the River Mersey, supporting them to use their bodies to notice how water moves through the city. The second, with Curator Florence Fitzgerald-Allsopp, Researcher/Geographer Joe Jukes and a local LGBTQIA+ group, will walk from Hauser and Wirth to Bruton (images below), where we will be spending a little time with the River Brue.

Flo is working with Spike Island in Bristol, and Hauser and Wirth Somerset, on an Ecotone focused fellowship, working with communities where land/water, and urban/rural meet, whilst Joe’s PhD focused on Queer Ruralities and the lived experiences of queer people in rural Somerset.

Somerset is a rich place for exploring wetlands past and future. Wild beavers have returned to the Brue in recent years and to other locations in Somerset, including the Heal Somerset rewilding site (images below), between Bruton and Frome, where I was recently invited to be part of a panel discussion on rewilding and diversity.

Somerset faces an increased risk of flooding due to Climate Breakdown, and is also shaping up to be something of a rewilding hotspot, whilst the value of beavers is increasingly recognised in managing river flows during both drought and flood. In an area that was drained for agriculture, much like the fens in east Anglia, the water is trying to return, bringing opportunities to return lost species, as well as threats to homes and current forms of agriculture (Cranes have already been reintroduced to the Levels, and discussions around the feasibility of reintroducing Dalmation Pelicans have begun).

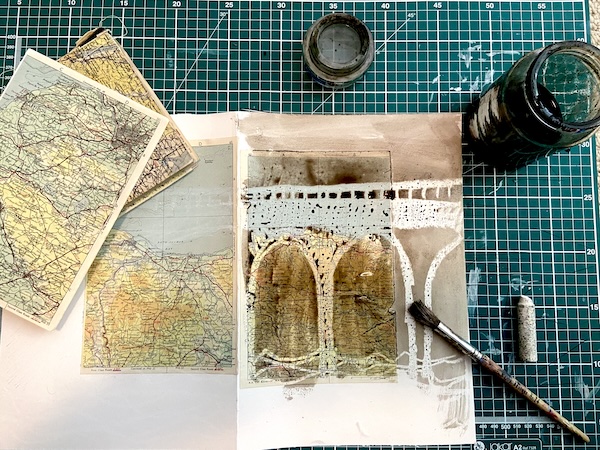

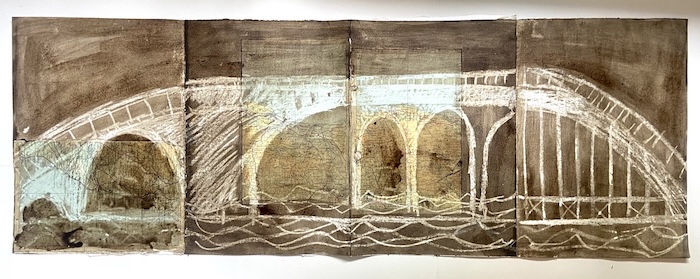

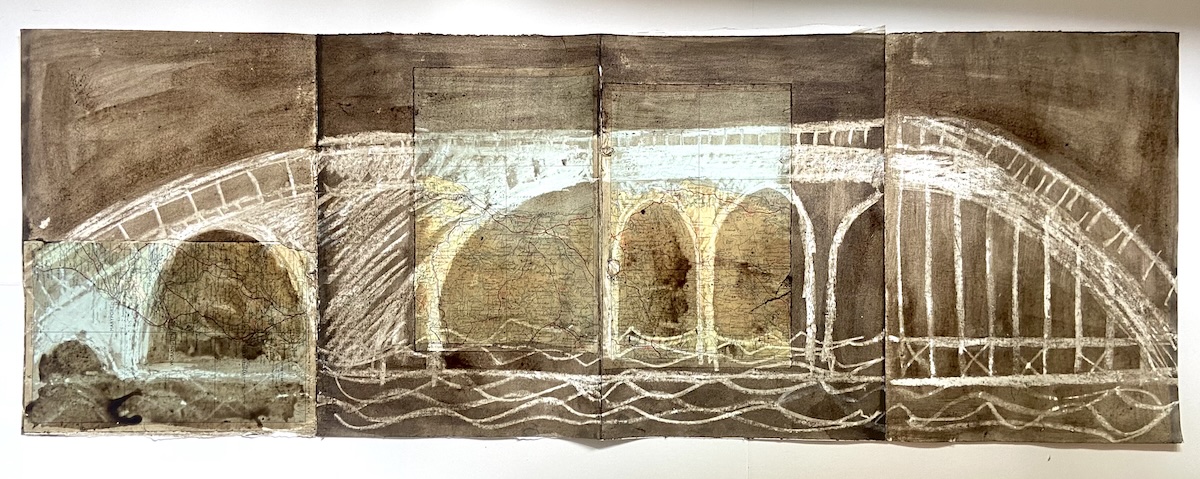

When I’m out cycling to bridges in the Vale of Pewsey, I take a bag of materials to draw with, recording what I notice and what the river shows me. I look out for signs of wetland animals, and how they interact with man-made structures, and take the documentation of my ‘noticings’ home with me in the form of photographs, drawings and found objects.

Back in my home studio I continue to play with bridge shapes and structures, through drawings that join a succession of different forms together, like a game of Exquisite Corpse. I’ve learned what I need to step into a state of flow, and how staying too long in ‘translator mode’ can fix my thoughts in too small an area, causing blockages that impact my wellbeing.

My body-mind makes sense of the world (and more specifically of rivers and our relationship with them) through this iterative process of walking, cycling, drawing, reading, writing and other forms of making, allowing elements of what I’ve noticed to sit alongside each other and find new connections, without pressure for them to ‘make sense’ in a neuronormative way.

‘…neuronormativity emphasises the idea that there is one right way to function and punishes anyone who diverges from this one right way.’

Queer River offers me ways to make sense of the world that suit my body-mind, and offers perspectives on river communities that go beyond the inherited and binaried concepts that have limited our thinking and caused so much damage in the past.

Its effects on me feel like a Stage Zero river restoration project, where human built structures that straighten/block a river are removed, allowing it to find its own path through the land, with a resulting complexity of habitat and a dynamism of flow that brings greater diversity and wellbeing.

One of the values of this way of carrying out research is its open-endedness, and so I’m not going to try and tie this all up neatly now, but instead leave it open, ready to return to again, when my thinking with bridges has developed further.

If you have any thoughts to add into the mix I’d be happy to hear from you… bridges, rivers, neurodivergence, it’s all welcome. Please comment below or get in touch and let’s see where it takes us.

One thought on “A Rivery Mind / Thinking with Bridges”